Tiffany Chen, National Conference Director (Speaker Relations)

Network Director

Tiffany Chen is a first-year medical student at the University of California, San Francisco. She was born in China and immigrated to Southern California at the age of 14. She completed her B.A. in Public Health and Molecular and Cell Biology at the University of California, Berkeley. Before medical school, she worked as a Clinical Research Coordinator at UCSF. Tiffany is passionate about serving immigrant and limited English proficiency (LEP) communities. Since her undergraduate years, she has volunteered as a health interpreter and served as a leader of the Volunteer Health Interpreters Organization at UC Berkeley, providing free interpretation and translation services across the Bay Area. At UCSF, she currently serves as the Co-Chair of the Asian Pacific American Medical Student Association (APAMSA) local chapter. Her academic and professional interests lie in clinical research, health disparities, and immigrant and women’s health. She is also deeply committed to mentorship and education to support disadvantaged populations. Ultimately, she hopes to combine her passions for research, advocacy, and community engagement to improve healthcare access and outcomes for the community.

Katherine Chua, National Conference Director (Speaker Relations)

Network Director

Katherine (pronouns: she/her/hers) is a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) who is part of the Program in Medical Education for the Urban Underserved (PRIME-US). She is a second-generation Chinese Filipino American from Santa Clarita, California. Katherine graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) with a B.S. in Human Biology and Society and a minor in Asian American Studies. As a medical student, she has been involved in student organizations that promote health equity in underserved communities across the Greater San Francisco Bay Area and bring to light the systemic injustices they face. She serves as co-chair of APAMSA at UCSF and co-president of the Filipino American Medical Student Association (FAMSA) at UCSF, where she strives to foster a supportive community of medical students and enhance diverse representation in medicine. Beyond health equity, she is also passionate about mentorship, ethnic studies, and expanding educational access. Katherine aspires to become a physician advocate who provides patient-centered care and partners with local leaders to create community-driven programs in underserved areas.

Jeanna Shaw, National Conference Director (Logistics)

Network Director

Jeanna Shaw is a medical student at the University of California San Francisco. She was born and raised in the San Francisco Bay Area in an immigrant household and has dreamed of becoming a doctor since she was 3 years old. She graduated Summa Cum Laude with Highest Honors with a degree in Human Developmental and Regenerative Biology from Harvard University, where she completed an honors thesis studying an induced pluripotent stem cell therapy for myocardial infarctions. Now a medical student, she serves as the Community Engagement co-chair and Advocacy chair at UCSF and is excited to step into the role of Logistics Co-director for the 2026 APAMSA National Conference. Jeanna is passionate about tackling healthcare inequities, particularly in immigrant communities with a specific focus on maternal healthcare disparities and structural barriers to healthcare literacy and access. In her free time, she loves art and music, running, and enjoying the outdoors.

Nelson Lin, National Conference Director (Logistics)

Network Director

Nelson Lin (he/him) is a medical student at the UC Berkeley – UCSF Joint Medical Program. His interests include language justice and cardio-metabolic health within AAPI communities. In his free time, he enjoys playing volleyball and making matcha lattes.

Brian Tangsombatvisit, National Conference Director (Communications)

Network Director

Matthew Kim, National Conference Director (Finance)

Network Director

Matthew Kim is currently a first-year medical student at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). He was born in Glendale, California, and raised in La Cañada. He completed his B.S. in Biomedical Engineering at UC Davis, worked as a Process Engineering Intern at Genentech, and spent his gap year at Stanford University as an Assistant Clinical Research Coordinator in the Department of Radiation Oncology, where he contributed to imaging-based cancer research and health access disparities.

In addition, Matthew has remained committed to service and mentorship throughout his journey. At UCSF, he currently serves as the Admissions Advisory Council Coordinator as a liaison for APAMSA and the admissions committee to support and connect incoming students who identify with the AANHPI community with school resources. He now acts as the NC Financial Director for the 2026 National Conference. He is passionate about equitable health access, community-centered care, and the intersection of medicine, technology, and education, and he hopes to continue his interests as he pursues a career in Radiation Oncology or Diagnostic Radiology.

Joint Statement on H.R. 1 by APAMSA, SNMA, LMSA, AMSA, SOMA, and MSDCI

On May 22, 2025, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 1 One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which contained disconcerting provisions aimed at cutting Medicaid funding by almost $700 billion over the next decade. Medicaid has been a central fixture for 83 million Americans, providing essential healthcare and long-term care for children, seniors, people with disabilities, and low-income adults. The Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion to adults who earn up to 138% of the federal poverty level ($21,597 for a single adult) has insured millions of Americans with health coverage. These potential changes will deprive over 10 million Americans from healthcare coverage through Medicaid and disproportionately affect communities of color.

Medicaid has been linked to increased access in rural and disadvantaged areas and improved health outcomes like decreasing all-cause mortality by almost 2% and lowering maternal mortality. In a recent report authored by the Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights and other national health organizations, Medicaid is the primary source of healthcare for almost 30% of people of color.

Medicaid has consistently enjoyed broad bipartisan support. A recent poll demonstrates that most Americans—Democrats, Republicans, and independents alike—favor maintaining and increasing spending on Medicaid access. Forty states across the political spectrum have opted into Medicaid expansion, recognizing the program’s role in improving health outcomes, supporting rural hospitals, and reducing uncompensated care. Despite the overwhelming evidence that Medicaid is extremely popular across the political spectrum and saves lives, House Republicans have moved to sacrifice public health in favor of funding tax cuts that primarily benefit the wealthy. The harmful provisions in H.R. 1 stand in contrast to the values shared by voters of all political backgrounds who believe Americans should not be denied care due to their income.

The bill will attempt to cut costs by

- Reducing the incentives and federal subsidies given to states for expanding Medicaid, specifically punishing any state that provides any health benefits or assistance to undocumented immigrants with lower expansion matches,

- Establish cost-sharing and copays of $35 for services provided to anyone above the federal poverty level ($15,650 for a single adult),

- Instituting stringent work requirements and eligibility verifications that burdens Medicaid recipients and state governments with more paperwork,

- Prohibiting Medicaid payment to nonprofits and providers that focus on reproductive health, family planning, and abortion services like Planned Parenthood,

- Removing gender affirming care as an Essential Health Benefit under the Affordable Care Act and prohibiting coverage for any Medicaid/CHIP recipient,

- Suspending rules that streamline application and enrollment into Medicaid and for patients who qualify for the Medicare Savings Program (covers Medicare premiums and cost-sharing for low-income Medicare beneficiaries).

We strongly condemn any legislation aimed at limiting equitable access to Medicaid or attacking access to abortion services and gender affirming care. Among the many destructive changes also embedded in H.R. 1, the elimination of federal student loans and loan forgiveness programs will severely limit access for students from all backgrounds to pursue careers in medicine. This bill proposes a lifetime cap of $150,000 for federal graduate student borrowing, specifically for those enrolled in professional programs. This will potentially force students to rely on private loans with less favorable terms and fewer protections, undoubtedly compounding the physician shortages in the very communities that rely on us.

At the heart of these proposed cuts lies an uncomfortable truth – healthcare is not a human right if equal access is not afforded to everyone regardless of socioeconomic class and immigration status. These actions go against the principles set by other nations, the World Health Organization, and the EU among others, highlighting the precarious path that the U.S. government is currently steering the country down. If passed in the Senate as is, the “One Big Beautiful Bill” will greatly harm patients across the United States and hamper the ability for physicians and other healthcare providers to serve their communities.

Call to Action:

To Senators – We call on all senators to reject this bill to protect the American public’s interest and maintain our great nation’s founding principles of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of happiness”

To Medical Students – we urge all medical students to contact their Senators in Congress and demand a No vote on the “One Big Beautiful Bill.”

Signed,

Asian Pacific American Medical Student Association (APAMSA)

Student National Medical Association (SNMA)

Latino Medical Student Association (LMSA)

American Medical Student Association (AMSA)

Student Osteopathic Medical Association (SOMA)

Medical Students with Disabilities and Chronic Illness (MSDCI)

Additional Resources:

Contact your Congressional Representatives: https://www.congress.gov/contact-us

More information about federal student loans changes: Official Statement and infographic

Call or email your Representative today with a call script from our partner organization, Vot-ER: https://go.vot-er.org/0mAQQu

For questions regarding this statement, please contact:

Rapid Response Director, Brian Leung at rapidresponse@apamsa.org

Win a Personalized, Signed Book by Ocean Vuong!

Enter to win a personalized, signed book from Ocean Vuong (unlimited entries!) to raise money for the LGBTQIA+ Scholarship for AANHPI Medical Students!

Three books, donated graciously by Ocean Vuong and his team, are being raffled off: On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Time is a Mother, and his brand new book The Emperor of Gladness!

Click here to enter!

For questions, please contact our LGBTQIA+ Director, Joey Hua-Phan (he/they), at lgbtqia@apamsa.org

Skin Cancer Screening Toolkit

Checklist and Links to Helpful Resources

- Review Skin Cancer Screening Protocol (also linked and described below)

- Skin Screening Training Guide

- Release Form Example

- Patient Health Information Form

- Event Sign-Up Template

- Materials List

- Community Member Demographic Collection

- Additional Resources and Links

Screening Skin Cancer Protocol

For a PDF view of the protocol below, please see this link: https://tinyurl.com/APAMSASkinCancerProtocol

At least 6 months before:

- Identify a community partner. This can include any institution, community cancer center, community health center, or municipal center that is willing to collaborate with you on your event.

- Identify physician mentors. Note that this is absolutely imperative for the success of your program. You must have a licensed physician participating at the event to sign off on screening results.

- Feel free to reach out to physicians outside of your institution. Working with community partners is strongly encouraged.

At least 5-6 months before:

- Research follow-up care options and referrals to the necessary practitioners as needed.

- Secure event location, obtain funding, gather educational materials, and print necessary health forms.

- Stay tuned for the release of our APAMSA Cancer Screening Grant to aid with funding.

At least 2 months before:

- Promote your screening in local newspapers, grocery stores, churches, and other areas in your community.

- Have online sign-up forms prepared and advertised so that clients can schedule an appointment.

- Start gathering all necessary materials (PPE, gowns, penlights, etc.).

At least 2 weeks before:

- Recruit and train volunteers – roles may include navigators, room turnovers, and desk clerks at check-in/check-out stations.

- Determine volunteer schedule. Go over protocol with them.

Day of screening:

- Volunteers hand out educational materials, register clients, and collect the proper forms (release forms, health info, self addressed envelopes).

2-3 weeks later:

- Contact everyone who participated in the screening via letters or phone calls regarding their screening results.

- Follow up with community partners and debrief on the event.

- Complete and submit Event Feedback Report to the APAMSA Cancer Initiatives Director.

Please contact cancer@apamsa.org in advance if you will be organizing a screening program and would like to participate in the national APAMSA effort to increase community access to cancer screening and education.

A full list of links to find healthcare access aid resources in your local area along with multi-language materials to utilize at your event can be found here.

Step-by-step protocol:

- Identify your population or community of focus. We highly recommend reaching out to local community organizations to discuss partnership.

- Identify a local physician (primary care, dermatologist, oncologist) who will serve as your mentor and oversee the screening.

- Important point: It is absolutely imperative you work with a physician for your program. Reports given to screened subjects must be signed by a physician.

- The American Cancer Society offers a list of databases to help allocate physicians in your area.

- Determine the cancer outreach and language needs in your area. Refer to this collection of multi-language cancer awareness pamphlets for examples of resources.

- Note: It is important to implement resources and an action plan that are inclusive of diverse skin tones and colors.

- Identify materials needed for the screening: Feel free to refer to this Materials List as a guide. Quantity and costs are subject to change.

- Secure funding to cover the cost of materials. APAMSA is setting up a Cancer Screening Grant application, so stay tuned for opportunities to gain funding.

- Research the following questions.

- Where can insured screening-positive clients obtain care?

- Provide referral information for physicians who see clients with suspicious skin lesions. The client’s own PCP is also sufficient.

- Where can uninsured screening-positive people obtain care?

- Provide information regarding clinics for the uninsured – find community health locations using this link.

- Are interpreters needed for your event?

- You may need to seek peer educators or AANHPI advocacy groups to recruit multi-lingual volunteers to serve as patient navigators, since many community health clinics do not have resources for interpreters for many Asian languages.

- Refer to the Additional Resources document for interpreter resources if needed.

- Where can insured screening-positive clients obtain care?

- Develop a client follow-up plan

- How will you ensure that clients who need further follow-up are able to contact any referrals made?

- E.g. additional phone calls to make sure the clients have contacted a primary care provider or have made an appointment.

- How will you ensure that clients who need further follow-up are able to contact any referrals made?

- Identify an appropriate screening location.

- This can be at a clinic that sees Asian patients, a cancer institute, a church, community center, or your local campus. For your screening event to go smoothly and efficiently, it is recommended that your venue has a waiting area, an area for check-in, at least two or more private rooms with seating, an area for check-out, and plenty of hallway space for multiple people to walk through.

- Obtain educational materials in English and Asian languages regarding skin cancer to distribute to the clients who come to your screening. Use existing materials from the CDC, American Cancer Society, The Skin Cancer Foundation, the American Academy of Dermatology, etc.

- Refer to this collection of multilanguage cancer awareness pamphlets for examples of resources.

- Print and organize all necessary forms: Our cancer screening toolkit contains examples of release forms and patient health info forms that you may utilize.

- If applicable, consider the need for translated versions of these forms based on the population you serve.

- Recruit and train volunteers; these may be students or members of community partner organizations. For a screening event that lasts multiple hours, you may assign hourly shifts to volunteers.

- These volunteers will be responsible for turning over rooms, serving as navigators, working at check-in and check-out stations, and some may participate in performing skin exams with a physician’s oversight. Assign a lead volunteer to be in charge of rooming and collecting forms.

- Advertise your event to members of the local community. Create registration forms that request contact information of clients who are scheduling an appointment. You may also request contact information of the client’s primary care provider (if applicable) to send results directly to them after your screening event. Distribute fliers to communal areas like grocery stores, churches, or recreational centers. See examples of fliers provided in our toolkit.

- Send out a reminder to all registered participants a week to a couple days in advance of their appointment time and event location.

-

- Have student volunteers ready at different stations.

- a. Check-in: Have clients fill out a health info form and a release form – see examples in our toolkit. Inform the client to take these two forms with them to the exam room. Keep an organized log of every client, their appointment times, and contact information to keep track of all clients who present to the screening. Have seating, clipboards, and pens available for those who are filling forms or are waiting to be seen.

- b. Screening Station: Each room should be turned over and prepped for every new client to be seen. A complete room should have all necessary PPE (gloves, masks, hand sanitizers), measuring tape for recording suspicious lesions, a clipboard and pen for the examiner, and a fresh gown for the client. Make sure each client is given plenty of time to change before being seen by an examiner.

- Use colored indicators on doors to track the status of each room: (1)vacant and ready for a new client, (2)occupied with a client who has yet to be seen, (3)occupied with both client and examiner, (4)vacant but needs to be turned over. You can use a binder ring with four different colored construction papers placed on a hook or doorknob.

- You should assign a volunteer as a lead who is in charge of rooming. This person assigns clients to vacant rooms and allocates an examiner to each client who needs to be seen. After each visit is complete, the lead should collect all Release forms from the client, and direct the client to a navigator to be escorted to check-out. The client should have only their Patient Info Form with them at check out.

- You should assign additional volunteers as navigator or room turnovers. Navigators are to escort clients from check-in to their screening station and back to check-out. Navigators should also double check that all client forms are handed to the lead. Room turnovers are to keep all rooms stocked with supplies and prepare a new gown for each client.

- Have student volunteers ready at different stations.

- Check-out: It should be recorded when each client has finished their screening and left the facility. Make sure to scan a photocopy of each client’s Health Info Form; they can take the physical copy with them for their own records or if they choose to present it to their provider at a follow up visit. At this point, volunteers can double check with the client that their logged contact information is correct in case you would like to follow up with them. Also confirm with the client that their PCP information is correct, or if they require referrals based on their insured status. Inform the client that their screening results will be sent to their established provider if they have one.

Overview of Screening Responsibilities:

- Positive for a suspicious lesion

-

-

- Recommendation: further testing, referral to a primary care physician, or follow-up at a clinic that accepts uninsured clients.

- For insured clients:

- Identify a physician/physicians in your area who specialize in skin cancer (dermatologists). Refer clients to these physicians, or encourage them to make follow-up appointments with their own primary provider.

- For uninsured clients:

- Ideally, identify and refer clients to a community health center dedicated to the Asian population.

- If unavailable, refer to a community health center, a clinic for the uninsured that provides Asian language services, an established navigator system, or a student run free clinic affiliated with your institution. Be aware of what referral systems and services are offered at your student run clinic.

- For insured clients:

- Recommendation: further testing, referral to a primary care physician, or follow-up at a clinic that accepts uninsured clients.

-

- Negative for suspicious lesions

- Recommendation: Encourage education and promote awareness.

-

-

- Educate clients that a negative screening result does not eliminate the possibility of skin cancer. Inform them of risk factors and prevention methods. Emphasizing sunscreen use is crucial. They should also be encouraged to perform self-examinations at home to identify any new or changing skin lesions which they can bring up to their primary care physician.

-

Client Follow-up Protocol:

- All clients with an established primary care physician should have their Health Info Form sent over to their provider’s office.

- It is ideal to follow up with everyone who participates in your screening to educate them about skin cancer and direct them to appropriate avenues for treatment.

- Important point: simply telling clients at your screening event to go see their primary care physician is not as effective as calling and writing to them directly.

- With direct communication, we can ensure that 1) clients understand what they need to do, and 2) they understand the reasons for doing so.

Examples of Client Follow-up Systems:

- Letters

- If you send out letters to your clients, make sure they are in English and appropriate Asian languages.

- Ensure that the language you use is readable and accessible to people with all levels of literacy. Avoid unnecessary jargon.

- Make sure your letters are customized with information regarding clinics, referrals, and skin cancer info.

- TIP: When you register people for the cancer screening, have them self-address an envelope to themselves that you will use to send them their results. This will minimize mistakes in mailing addresses.

- Letters and Phone calls

- Sending letters and following up with phone calls is a better way of making sure the people understand their screening results.

- Make sure that if you make phone calls you have people who can speak the language of the person you’re calling, either through recruiting volunteers who speak other languages or using phone interpreter services.

- If you mail a letter, try to follow up with a phone call 2 weeks later to make sure they understand the letter and encourage follow-up. Then, make a follow-up call 3 months later to see if action was taken. The downside to making phone calls is that you can’t give medical information to anyone except for the person you screened, so you may have to call back several times.

Handling Patient Info:

- You should keep all physical copies of signed Release Forms on file for proof of HIPAA compliance. Any client is allowed to request a copy of their Release Form.

- All clients should leave the event with the physical copy of their Health Info Form after you scan a photocopy and store it digitally in a private location. Ensure that only your institution, club executive board, and/or partnered organization’s administrative members have access to these documents. You may send copies of Health Info Forms to your clients’ primary care physicians with each client’s permission.

- Make sure to discard all physical copies of sensitive documents appropriately if they are no longer needed (i.e. by paper shredding).

It is recommended before you proceed with anything to talk to your schools and partnered organizations regarding the best way to handle this.

While there is very little risk involved with skin cancer screening, every institution and health organization has different policies which you must understand before proceeding with any service that informs patient care. This is another reason why the first and most important step is to secure a licensed faculty/ physician advisor to oversee your screening.

We’d love to hear about your experience using this toolkit! If you have any thoughts you’d like to share regarding what we’ve done well and where we can improve, please fill out this feedback form.

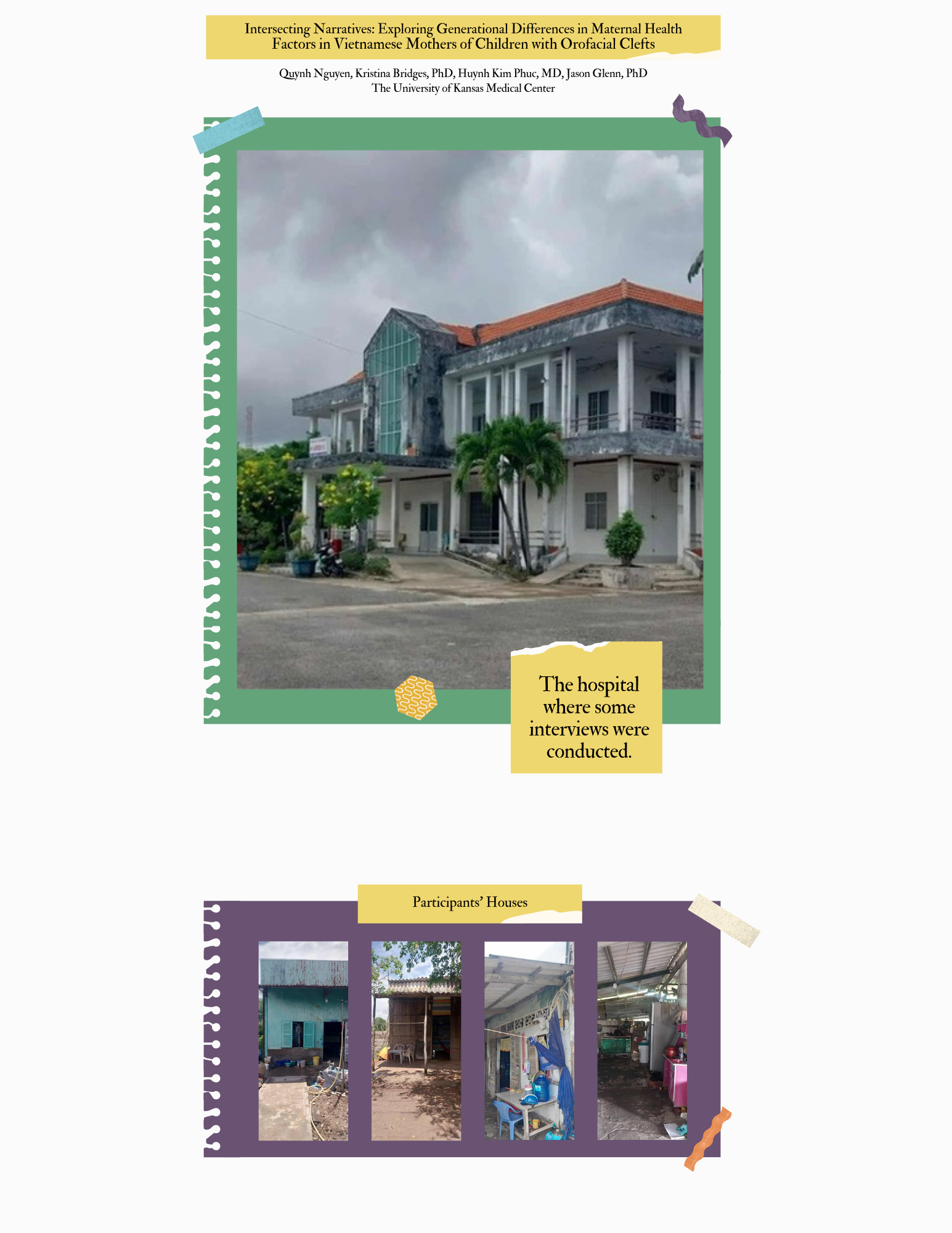

Intersecting Narratives: Exploring Generational Differences in Maternal Health Factors in Vietnamese Mothers of Children with Orofacial Clefts

Clefts Without Borders

The voices of the women I interviewed will stay with me for a long time. They’ve reshaped how I think about healthcare, equity, and the role of a physician. And they’ve deepened my commitment to becoming not just a doctor, but a better listener, advocate, and bridge between cultures.

Quynh Nguyen, MS3 at The University of Kansas Medical Center